(gap: 2s) In the summer of 1954, our small universe was comprised of two houses on Maple Lane. My family—myself, Susan, my elder brother David, and my younger sister Linda—resided next to the Johnsons, whose children were as familiar to us as our own relations. There was Thomas, a boy of my own age with a penchant for mischief, his younger brother William, and their elder sister, Barbara, who presided over our group with the authority of a headmistress. Together, we formed a rather untidy assembly, our days filled with games of hopscotch, secret handshakes, and the sort of elaborate plans only children could devise. Yet, one Sunday, our inexhaustible energy would lead us into a misadventure of such magnitude that it would be recounted in our families for years to come.

That particular Sunday commenced with a heat so oppressive that the very air seemed to quiver, and the tar upon the road became soft beneath our feet. The church bells tolled, but the prospect of enduring a sermon in our finest attire was intolerable. With a series of meaningful glances, we conceived a plan: we would abscond to Willow Pond, our secret haven, where the water was cool and the world seemed far removed from the strictures of adulthood. No one considered seeking permission. We slipped away, shoes in hand, and plunged into the pond, our laughter and shouts echoing as if the day belonged to us alone. Time passed unnoticed until the sun began to lower, and a sense of foreboding crept upon us. We hurried home, hair dripping and hearts racing, only to find our mothers—Mrs. Johnson and my own mother, Margaret—awaiting us, arms folded and expressions severe.

We were assembled in the hallway, arranged by age, the youngest at the front. The air was heavy with the scent of lemon polish and the anticipation of impending retribution. Behind the closed door of my parents’ bedroom, our mothers conferred in low, urgent voices. We fidgeted, eyes wide, as our fate was determined. At last, the door opened, and my mother emerged, her countenance resolute. “Each of you shall be punished,” she announced, her tone as unwavering as the church organ. “This is a lesson you shall not soon forget.”

Without delay, she reached for Linda, my little sister, who immediately began to weep, clinging to the doorframe as though it were a lifeline. “No, Mama, please! I am sorry, I shall not do it again!” Linda cried, her small hands grasping the wood. But Mother was steadfast. She gently loosened Linda’s grip, lifted her up, and carried her into the bedroom, the door closing with a soft, ominous click.

Silence descended, broken only by Linda’s muffled sobs. Then came the unmistakable sound of a spanking—each smack reverberating down the hallway like a judge’s gavel. “Young lady, you know better than to run off in such a manner,” Mother’s voice carried through the door, stern yet not unkind. Linda’s cries grew louder, a heartrending chorus that caused William, the youngest Johnson, to whimper in sympathy. We all stood motionless, the reality of our predicament settling upon us.

At length, the door opened. Linda, her face flushed and tear-stained, was gently turned to face the wall, her shoulders trembling. She stood there, the very picture of misery, as William was summoned for his turn. Mrs. Johnson knelt, smoothing William’s hair. “Be brave, dear. It will be over soon,” she whispered, but William’s lower lip quivered as he shuffled forward.

William’s face was already streaked with tears as he was led in. His cries began before the first smack, and soon the air was filled with his wails, mingling with the steady rhythm of discipline. “I am sorry, Mama! I shall not do it again, truly!” he sobbed, his voice breaking. When he emerged, he joined Linda, both united in their sorrow, sniffling and rubbing their eyes.

Next was Thomas. My mother took him by the ear, leading him into the room. The rest of us exchanged anxious glances, imagining the worst. Thomas attempted to appear courageous, but his composure faltered as the door closed behind him.

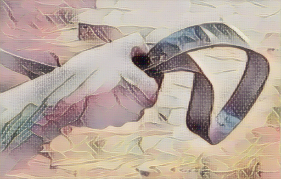

Suddenly, Thomas’s voice rang out, high and desperate: “No, not the slipper! Please, not the slipper!” We all shuddered. The slipper was infamous—a tool reserved for the gravest offences, a sturdy house shoe with a hard sole, wielded by mothers since time immemorial. It was a faded blue, the sort of slipper every father seemed to possess, with a thick, rubbery sole and a worn corduroy top, the fabric soft but the bottom unyielding. When it struck, it made a flat, echoing smack, and the sting would blossom hot and sharp, leaving a memory that lingered long after the sound faded. The slipper always smelled faintly of dust and old linoleum, and in that moment, it seemed impossibly heavy, as though it bore the weight of every misdeed we had ever committed. The sounds that followed were swift and sharp, Thomas’s pleas growing more frantic with each smack until they dissolved into sobs. “I promise, I shall never do it again! Ow! I am sorry, I am sorry!”

The tension in the hallway was palpable. Each of us attempted to appear brave, but the fear was unmistakable. The slipper, once a distant threat, now seemed terrifyingly real. I could almost feel its sting merely from the sound.

The smacks slowed, then ceased. Thomas emerged, his face blotchy, eyes downcast, and took his place beside the others, his bravado vanished. He wiped his nose on his sleeve, avoiding everyone’s gaze.

Then it was my turn. My heart pounded as I stepped into the room. Mother wasted no time, pulling me over her lap with practiced efficiency. Mrs. Johnson observed, arms folded, her lips pursed in stern approval. The room felt smaller, the air thick with the scent of talcum powder and the weight of consequence.

I caught a glimpse of the slipper before it landed—a battered, blue corduroy object, its edges frayed from years of use, the sole thick and unyielding. The rubber bottom was cool and smooth to the touch, but when it struck, it was like a jolt of fire, the sting spreading across my skin in a hot, prickling wave. The slipper was heavy in my mother’s hand, and each smack seemed to echo with the authority of every mother in the 1950s. For a moment, I was too shocked to cry, but as the blows continued, the pain increased until I could not restrain myself. “Ouch! Mama, please! I am sorry! I shall not do it again, I promise!” I kicked and pleaded, but Mother held me firmly, determined to make her point. “You must learn to listen, Susan. This is for your own good,” she said, her voice steady, almost weary.

Tears streamed down my cheeks as I begged for mercy, but the punishment continued until, at last, it was over. I was helped to my feet, legs trembling, and sent to join the others, my pride as bruised as my person. I could feel the heat of embarrassment burning on my face as I stood in line, sniffling.

Now it was Barbara’s turn. She protested loudly, insisting she was too old for such treatment. “I am nearly a teenager! You cannot do this!” she cried, but her objections were disregarded. Mrs. Johnson’s voice was firm: “You are never too old to learn right from wrong, young lady.” Barbara was led in, her cries echoing down the hall. The slipper was applied with a thoroughness that left no doubt as to the seriousness of her offence. “You shall not set a poor example for your brothers,” Mrs. Johnson scolded between smacks.

Barbara’s punishment seemed interminable, her shrieks filling the house. “I am sorry! I am sorry! Please, Mama, I shall be good!” When she finally emerged, her face was streaked with tears, her composure utterly lost. She joined our growing line of chastened children, head bowed, her usual confidence entirely absent.

One by one, we stood in our sorrowful procession, each of us nursing our wounds—both physical and otherwise. The lesson was being learned, whether we wished it or not. The hallway was heavy with the sound of sniffling and the occasional hiccuping sob.

At last, it was David’s turn. He attempted to appear brave, puffing out his chest, but his courage deserted him as he was led into the room. His eyes were wide with fear, and when the spanking began, his cries were the most pitiful of all.