Before I recount that remarkable Sunday, allow me to introduce the principal characters in my tale, as though you were meeting them in the pages of a Roald Dahl story, each one as distinct as the chime of the church bells on a brisk morning.

First, there is Margaret, my mother. Margaret is tall and dignified, her presence both commanding and comforting. Her kind brown eyes seem to perceive any untruth or mischief, and her gentle smile can become stern in an instant if one steps out of line. She always wears her hair in a neat, practical bun, and her dresses are simple yet immaculate, often adorned with a brooch or a string of pearls. Margaret is the sort of mother who bakes the finest scones in the village—golden, crumbly, and warm from the oven, filling the house with a delightful aroma. She possesses an uncanny ability to sense when one is up to something, and her sense of fairness is matched only by her determination.

Next is George, my father. George is a cheerful, broad-shouldered man with a hearty laugh that fills the room and a fondness for tweed jackets, which always seem to carry the faint scent of pipe tobacco and the outdoors. He is often away on business, but when he is home, the house is enlivened by his stories—tales of distant lands, daring adventures, and clever inventions. His hands are strong and capable, able to repair anything from a leaky tap to a broken toy, and he has a twinkle in his eye that suggests mischief or a spontaneous game of cricket in the garden. His presence is reassuring, a steady anchor in the sometimes unpredictable sea of childhood.

Mrs. Brown, the crossing lady, is a fixture in our neighbourhood. She is a sturdy, broad-shouldered woman with rosy cheeks that glow even on the coldest mornings, and she is always clad in her bright yellow coat, making her visible from afar. Her stop sign is held high and proud, a symbol of her unwavering dedication to the safety of every child who crosses her path. She greets each child by name, her voice warm and clear, and her laughter is infectious. Yet, she is fiercely protective, and her rules about road safety are absolute. Beneath her brisk exterior lies a heart as generous as her smile, and she is known to offer a sweet to the children on special occasions.

Lastly, there is Constable Harris. He is a tall, upright policeman, his uniform always immaculate, and his helmet polished to a mirror shine. His face is serious, almost stern, but if one looks closely, there is a glimmer of kindness in his eyes, especially when he believes no one is watching. He takes his duties with the utmost seriousness, patrolling the streets with a purposeful stride, but he is always ready to lend a hand or offer a word of advice. He believes in teaching lessons, not merely enforcing rules, and his presence commands respect from all.

As for myself, I was just beginning to find my place in the adult world, standing on the threshold between childhood and maturity. I had recently left school and commenced my first position in an office, a world of ledgers, typewriters, and the steady tick of the clock. Yet, despite my new responsibilities, I still managed to find myself in difficulty from time to time, as you shall soon discover.

(short pause) My final reprimand from Margaret, my mother, remains etched in my memory for all the wrong reasons—particularly as I was no longer a schoolboy, but a young man, eager to prove myself in the world.

Margaret and George, ever thoughtful, had purchased for me an old BSA Bantam 125 motorbike—a sturdy, well-loved machine with a faded green tank and a seat worn smooth by years of use. It was my pride and joy, a symbol of newfound independence. In those days, one could ride such a machine without any formal training or examination, and I delighted in the freedom it offered, the wind in my hair and the open road before me.

One morning, with the sun barely peeking over the rooftops, I found myself running late. The air was crisp, and the streets were alive with the bustle of children heading to school, mothers conversing at garden gates, and the distant chime of the church clock. As I approached the crossing, Mrs. Brown stood at her post, her yellow coat bright against the grey pavement, her stop sign raised high. I carefully made my way to the front as the children gathered, their laughter and chatter filling the air. Believing it safe, I edged forward, my heart pounding with impatience. The stop sign was still raised, but I persuaded myself it was permissible to proceed. As I moved off, Mrs. Brown turned towards the pavement, and I narrowly missed her, the motorbike’s engine sputtering as I hurried away. My cheeks flushed with guilt, but I dismissed the thought, eager to make up for lost time.

After a long day at the office, the clatter of typewriter keys and the scent of ink still lingering in my mind, I put my motorbike away in the shed and entered through the front door. The house was quiet, save for the faint murmur of voices in the lounge. George was away on business, but I could hear Margaret’s unmistakable tone—firm, measured, and unmistakably serious. As I stepped into the lounge, Margaret called my full name, her voice echoing through the hallway. She only ever did so when I was in real trouble. I opened the door to find Margaret seated upright, her hands folded in her lap, Mrs. Brown standing by the fireplace, her cheeks flushed with indignation, and Constable Harris, his helmet resting on his knee, his expression grave. Mrs. Brown had clearly recognised me, which was hardly surprising, as I had passed her every day on my way to school for years, exchanging nods and the occasional smile.

Margaret fixed me with a steady gaze and asked if I knew why they were there. I nodded, my heart sinking. She explained that Mrs. Brown had spoken quietly to Constable Harris, who had been at the school that morning, and together they had decided not to pursue the matter formally, but to speak with Margaret first. If they felt I had been suitably punished, the matter would be dropped, and my record would remain unblemished.

Constable Harris then delivered a lengthy, measured lecture on the dangers of my riding, his voice calm but firm. He described, in vivid detail, the accidents he had witnessed, the lives changed in an instant by a moment’s carelessness. He warned me that I was fortunate not to be prosecuted, and that my actions could have had far more serious consequences. Mrs. Brown, her eyes shining with unshed tears, reminded me that her own husband had died in a road accident, her voice trembling with emotion. She was understandably upset, her words sharp and unforgiving, and she made it clear that she wished to see me punished most severely. At this point, my confidence faltered, and I began to fear the worst.

Margaret then announced my punishment. I was to be forbidden from using my motorbike for a week—a sentence that felt interminable. My commute would now be longer and more expensive, as I would have to take the early bus, standing in the cold with the other commuters, my pride wounded as much as my wallet. She then confirmed my fears by telling me I was to be chastised, her voice leaving no room for argument.

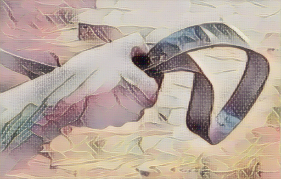

I protested, my voice trembling with desperation, but it was made clear that I was fortunate not to be facing the magistrate—only Mrs. Brown’s kindness had spared me. I pleaded that I was too old, that such punishments were for children, but Margaret was unmoved. She left the room and returned with a leather strap, much like the one Aunt Edith used. (short pause) I remember it vividly: the strap was a deep, almost mahogany brown, its surface smooth but for a few creases from years of careful storage. It was about two feet long and a couple of inches wide, cut from thick, heavy leather that felt cold and unyielding to the touch. The edges were rounded and darkened, and the handle bore the faint imprint of Aunt Edith’s initials, pressed into the leather. When Margaret flexed it in her hands, it made a quiet, ominous creak, the sound sending a chill down my spine. The strap had a certain weight to it, and just the sight of it was enough to make my knees weak. She explained that Aunt Edith had given it to her many years before, but she had never felt comfortable using it. Today, however, was different. The room seemed to grow colder, the shadows lengthening as the afternoon sun faded behind the curtains.

I knew it was pointless to argue and prepared myself, my hands trembling as I tried to steady my breathing. Yet, that notion was quickly dispelled, for Margaret insisted I face my accuser while she fetched a chair from the kitchen. The chair was a sturdy, high-backed affair, its seat polished smooth by years of use. She placed it so that my back was to Mrs. Brown and Constable Harris, and instructed me to bend over it, gripping the seat tightly. My heart pounded in my chest, and I could feel the blood rushing to my face as I assumed the position, my legs trembling beneath me.

Margaret’s demeanour was resolute,

Mother stood alongside me and I felt the strap touch my buttocks. It soon lashed down hard and Mother continued at a steady pace, causing me to cry. Then she hesitated, and I was hopeful that the punishment was over. No such luck – Mother handed the strap to Mrs Jones, who needed no encouragement. She whacked just as hard and much faster, causing me to yelp as each stroke landed.

After about eight whacks she stopped. I was ordered to get back in position by Mother, and Mrs Jones handed the strap to the policeman. I was told that if I had gone to court, I would have got at least three points on my licence so I was to receive three whacks from the officer.

He was very enthusiastic and whacked me much harder than the women, making me yelp even louder. Finally, Mother took the strap and told me to stand and apologise to Mrs Jones. I did as requested, and hoped I could leave. But no – Mother ordered me to stand in the corner facing them, hands on my head, while they finished their tea and cake. I was so embarrassed and they seemed to take forever as they chatted a lot.

Eventually she and the policeman left and Mother told me to go to my bedroom.

The week seemed very long and I certainly learned from the experience. I rode the motorbike with much more care after that. The whacking had been my most embarrassing and painful – Mother very rarely spanked me and it was usually either her hand or a wooden spoon.

About a month later, I bumped into the Mrs Jones in town. She was really friendly and we went for a coffee. We had quite a laugh about the whacking and we seemed to be getting on well, considering that she was twice my age.

That was my last whacking from Mother, but not my final dose of corporal punishment. I had to stay away for three months on a training course and got a few whackings there – but that’s a story for another time.